As recited in my essay "Lady Chatterley Stoned" (published by Lester Grinspoon), I was standing in the darkness on the front lawn on a

cold night in early January of 1974 when my life began to change. The grass was caked with ice that had been around for weeks. The

date was before January 12th, when I would turn 32. My car, which was in the dark driveway, was a 1960 Chevrolet Impala with

a big engine and an empty gas tank. The first energy crisis was upon the land, and no gas was available.

There was no telephone in the house, and no furniture except for a rug, blanket and a table lamp, all of which I had

arranged on the floor of the smallest bedroom. I was living there until I painted the interior of the house.

I had also brought along a copy of "Lady Chatterley's Lover," which had been banned in the United States until a few years

earlier; I had brought it along for the purpose of thumbing through it and finding "dirty words." I did not know it, but I

was at that time illiterate in the following way:

I could see and read simple 4-letter words okay -- i.e., "decode" them, which is a term of art within the reading science

industry. Words like "shit" and "fuck" I could read, and I hoped to find them in Lady Chatterley for this sole purpose: to be able

to say I had seen the dirty stuff in "Lady Chatterley's Lover." However, the reading style or method I had been

taught in school was one that involved the "sounding out" of syllables which, when I encountered such long and complex

words as "determine" or "illiterate," I would, by habit, work through them syllable by syllable till the meaning of the word

entered my mind. It was a method that caused me to pause, in at least every other sentence, and thus never establish the kind of

"flow," reading flow, that is necessary to real reading. By the time I "decoded" a word such as "intimidate" or "regiment," I

would have forgot the main idea of the sentence along with whatever general comprehension I might have had of the entire

text. But that was how I had been taught to read -- and taught and taught and taught: I had spent years of school-day afternoons

and summer holidays in remedial reading classes, always being shown how to sound out syllables.

Prior to the cold night in question, I hadn't used any marijuana in months or maybe a year or more. And as I felt the

extreme of winter loneliness on that cold night in 1974, with the street lights glinting off the icy lawn and the dead car, I put

my hands in my coat pockets, and there, in the bottom of the one on the right, I felt the remains of a joint. Half a joint.

I noted it, but was otherwise unmoved and my mood was unchanged.

About 30 minutes or so later, the joint had offered up a couple of smoky inhalations and I was lying on my side on the

rug, in the light of the table lamp on the floor with me, thumbing through "Lady Chatterley's Lover." Minutes might

have passed, or maybe only tens of seconds. I opened the book at several random places, scanning the pages for the desired dirty

letter patterns. -- Then a mental image, one as clear at any photographic image or as vivid as actually seeing it, appeared of

a stone-paved path leading to the door of a cottage with a thatched roof. (I would place an image here of a thatched-roof

cottage, but none of the ones available in Google Images compares in silent mood to the warm image that is still in my mind.)

Such a thing had never happened before, a mental image being provoked by written words. I thought I had discovered a new way

of reading. Until that evening -- and actually for some years after that evening -- I had been under the impression that I had

known how to read as well as anyone else, except that I was slower.

I had attributed that slowness of reading comprehension to a slowness of mind, a kind of stupidity that I mostly tried to mask

from others, who I considered to be smarter. (In high school and college, others, the smarter others, always had correct answers

to the teachers' questions, answers which had come from written sources that had, in effect, been mostly inaccessible to me. I

knew I was a slow reader, and it had made me think I was mentally inadequate, despite my ability to get high scores on the kinds of

tests that were used to gauge intelligence -- tests that rarely involved long and complex words and comprehension of whole

sentences.)

Despite that sense of mental inferiority, I had by that point in my life acquired a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering. I had a perfect 3.0 GPA in my science and engineering classes in college because, I assume from this present vantage, that the basic principles were readily evident

to me; and the mathematics, which I was not all that good at, I was at least sufficiently good at it. However, in such subjects

of study as English and history, my GPA was somewhere just under 2.0.

I had, by that winter evening in 1974, also taught math and physics for five semesters at a Jesuit high school in Washington,

D.C. The headmaster had called me a "natural teacher." And, by being "a teacher," I had overcome at least part of my feeling of

intellectual inferiority.

That teaching job had come right after college. I taught through 1965 and 1966 and the spring semester of 1967. I had

during that time applied to law school, as my friends were doing then, and I was accepted at Georgetown Law Center. But whereas

most of my friends were able to maintain their study of the law, I was out within a week: I could not comprehend the first

sentence of the first case book I was required to read. The specific case was one that involved a murder and a furnace and

evidence of an incinerated body. That was as much as I could get from the written material even after hours of attempted

comprehension, but I could not get any details or determine any of the "facts" that would have been relevant to any discussion of

legal issues.

After that evening with Lady Chatterley in 1974, I would smoke marijuana in the evenings after work and read while stoned. Not

until about eight years later did a psychiatrist point out that I had not discovered a new way to read, but rather that I

had simply learned to read. He, the psychiatrist, happened to be a reader. I was lucky in that.

The vaporizer idea came along in this way: I couldn't get used to the sore throat that came with smoking marijuana. And in the

mid Seventies, the engineering consulting company I was working for sent me to Baltimore to look at a solid waste plant that

Monsanto had built for the city. The plant was designed to separate glass from metal in the waste stream and also to

generate combustible fuel gases from the paper and plastic portions of the waste stream; the fuel gas was to be used to

generate steam heat for some of the downtown buildings. Or such is my memory. (My job was to write a proposal to the city of

Baltimore on an efficiency study of the plant, the cost of running it versus the benefits of the steam heat and the outflow

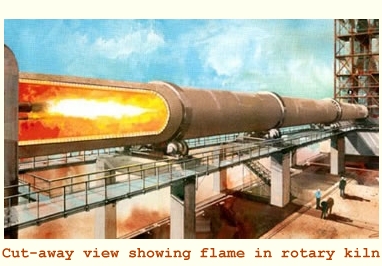

of glass and metals.) The plant consisted of a rotary kiln of the sort used to make concrete.  Solid waste, consisting of paper, plastics, bottles and cans, was loaded into the upper end

of the inclined rotary kiln, while a jet of burning fuel oil was blown in at the lower end. The idea, which was immediately clear

to me, was to heat the cellulosic and plastic portions just enough to break large molecules into smaller ones so as to

comprise a gas that could piped elsewhere and burned for heat. That is to say, the idea was not to burn the solid waste but

rather only to heat it just high enough to break large molecules into smaller ones and evaporate the waste's volatile fractions,

most of which could be used as fuel gas. Solid waste, consisting of paper, plastics, bottles and cans, was loaded into the upper end

of the inclined rotary kiln, while a jet of burning fuel oil was blown in at the lower end. The idea, which was immediately clear

to me, was to heat the cellulosic and plastic portions just enough to break large molecules into smaller ones so as to

comprise a gas that could piped elsewhere and burned for heat. That is to say, the idea was not to burn the solid waste but

rather only to heat it just high enough to break large molecules into smaller ones and evaporate the waste's volatile fractions,

most of which could be used as fuel gas.

In looking at the kiln and considering the processes of pyrolysis and evaporation, it seemed likely that marijuana could

likewise be heated to less than its combustion temperature so as to drive off -- to evaporate or vaporize -- the volatile desired

substance or substances into an inhalable airstream, one that contained none of the irritating by-products of combustion.

The first test model I built with glass lab wear from the company's laboratory. I used a 1,000-watt piece of Ni-chrome

heating element from an old toaster. It operated just long enough before melting down to show that the "active aspect" of

marijuana could indeed be evaporated as I had anticipated. I have not smoked in 20 years. Well, maybe a couple of times in

the company of others, but never when I want to be high with the intention of reading.

Send comments to Bob

Back to Flash Evaporator Home Page

|